If you are curious about this, you have probably already experienced the intense emotions that accompany serious romantic relationships, married or otherwise. From the excitement of the early days, to the sense of comfort and security that accompanies commitment, to the anguish of feeling separate when something goes wrong, our most intense emotions occur in the context of our intimate partnerships. A growing body of research is revolutionizing couple therapy by demonstrating that these emotions are part of a neurobiological system in humans, and other mammals, that is the basis of social bonding (Carter, 2005; Insel & Young, 2001; Young et al, 2011). To the list of other instinctive needs, such as the needs for food and sleep, we can now add the need for an emotionally secure relationship, or attachment, with another human being. In adulthood, disruptions in the security of these partnership attachments are at the root of emotional distress in couples. Emotionally focused couple therapy (EFT) specifically targets these intense attachment-related distress-emotions with a structured, step-by-step therapeutic method. The focus on emotions that are signals of attachment-related problems and the structured method are what sets EFT apart from other couple therapies.

Part 1: Emotions

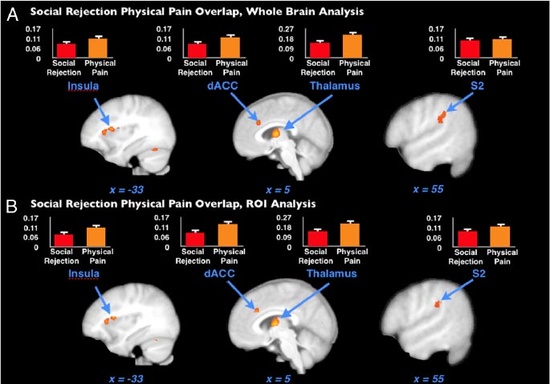

The emotions, joy, fear, anger, sadness, shame, surprise are part of the universal experience of being human — even being mammalian (Panksepp, 1982). They are part of a neural system that evolved over millions of years to alert us to situations in our environment that require action. Fear cues us to protect ourselves. Calmness tells us that we are safe and can let down our guard. Without emotions to alert us to the dangers in our environment, we don’t survive. Emotions are adaptive as part of the fight – flight – freeze response when we perceive and anticipate danger (Panksepp, 1998). Put simply, emotions are part of a psychobiological self-protection program.

Most of us are more familiar with the protective features of our peripheral nervous system. After burning their fingers once or twice, children learn quickly to avoid touching a hot stove. The experience of hot and cold, soft touch and deep pressure signal us about the safety of, first, our skin – our first line of defense. If you submerged your hand in boiling water, the burning pain instantly signals you to remove your hand from danger. Similarly, we know that we are hungry because of sensations (and noises!) in our stomachs. When our eyelids close involuntarily, our bodies feel heavier than usual, and we find it hard to concentrate, we conclude that we are tired. These sensory experiences are messages about the status of our physical safety and well-being. We stay healthy when we respond to these cues by doing what our body is telling us: eat now, sleep now, don’t put your hand in boiling water!

Likewise, the emotions we feel in our intimate relationships signal us about our psychological safety and well-being. Calmness and relaxation, breathing easily, and a sense of peace with our partner typically signal that all is well in the relationship: the need to feel safe and secure with our partner is being met. And, like burning pain and hunger, that knot in your stomach may reflect your uncertainty about whether your mate really loves you. You may notice a heaviness in your chest when you feel sad and unimportant to your partner. Or you may feel numb or dead inside, trying to anesthetize yourself against the despair of isolation from your spouse. These are psychophysiological messages that something is amiss in our attachment relationship: our need to feel safe and secure is not met. The signal means do something to reestablish a safe, secure connection. It is an elegant system that works well, if we pay attention to the psychophysiological messages and take action.

System failure has a few common causes. We may not be paying attention to the emotional sensations and experiences. We may note the sensations, but not know how to decipher their meaning or know what to do about them. Or our actions may be perpetuating the distress. When both members of the couple struggle with understanding their attachment emotions, and act in ways that unwittingly increase the distressing emotions, a negative interaction cycle forms. Quickly, the couple’s cycle becomes habitual, automatic, and painful. Though they want to feel close and connected, they end up feeling distant and isolated.

That is where EFT comes in. It reconfigures the habitual cycle that create distress and distance by targeting the emotions that drive the cycle. The goal of successful EFT is a new interaction cycle that is attuned to and meets the attachment needs of both partners (Johnson, 2004). The research shows that couples who successfully complete EFT retain the benefits of treatment as long as three years after it ends (Halchuk et al, 2010) and, in some cases, show continued improvement even after treatment ends (Clothier et al, 2002).

To read more about attachment needs and the negative cycles that are typical among couples, read Hold Me Tight by Susan Johnson.

Coming soon: Part 2, What is Attachment?

References

Broad KD, Curley JP, Keverne EB. Mother-infant bonding and the evolution of mammalian social relationships. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, Biological Sciences 361(1476): 2199-2214, 2006.

Carter CS. Biological perspectives on social attachment and bonding. In: CS Carter, L Ahnert, KE Grossman, SB Hrdy, ME Lamb, SW Porges, N Sachser (Eds), Attachment and Bonding: A New Synthesis (pp 85-100). Boston: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 2005.

Clothier P, Manion I, Gordon-Walker J, Johnson SM. Emotionally focused interventions for couples with chronically ill children: A two year follow-up. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 28:391-399, 2002.

Halchuk RE, Makinen JA, Johnson SM. Resolving attachment injuries in couples using emotionally focused therapy: A three-year follow-up. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy: Innovations in Clinical and Educational Interventions 9(1):31-47, 2010.

Insel TR, Young LJ. The neurobiology of attachment. Nature Reviews 2:129-136, 2001.

Johnson SM. The Practice of Emotionally Focused Couple Therapy. New York: Brunner-Routledge, 2004.

Panksepp J. Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions. New York: Oxford, 1998.

Panksepp J. Toward a general psychobiological theory of emotions. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 5(3): 407-467, 1982.

Young KA, Gobrogge KL, Liu Y, Wang Z. The neurology of pair bonding: Insights from a socially monogamous rodent. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 32(1):53-69, 2011.

copyright Ann-Marie Codori 2012

Share this post